The Sudbury Basin, Sudbury Mining District and surrounding area still has a lot to offer for mining, according to the new district geologist.

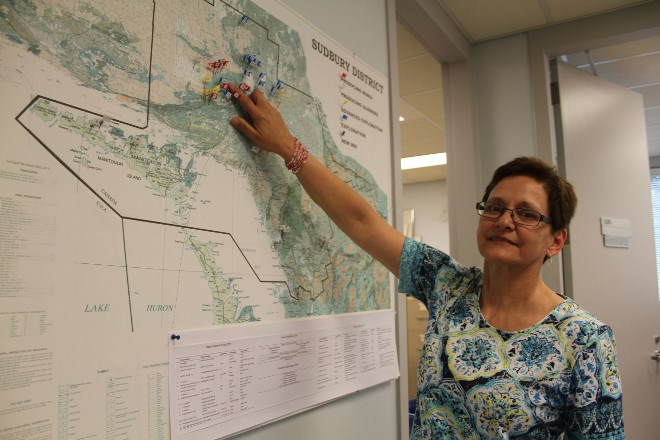

“The basin has always been a fascinating place for geologists,” said Shirley Peloquin at the Ontario Geological Survey office inside the Willet Green Millar Centre.

“It's still proving to be a very rich place for nickel and other reserves of minerals and this could go on for decades. As demand shifts for other minerals prevalent in the area we are always mapping, surveying and cross-checking with historical data. We are always finding new deposits.”

She explained much of the underground of the basin, as well as areas northeast of the basin to the Quebec border, are largely untapped. Much of the focus has been on the easier to extract surface deposits. From a casual view it would look like deposits are dwindling, but the opposite is true.

“It looks like there are few mines, but how many places do you know have eight working mines in them? There are many more underground deposits that go deeper than we used to believe,” she said.

“In the past, it wasn't feasible or financially worth it to extract these deposits. As demand rises and falls and technology improves to make it economical, companies are seeking out these deposits.

“As one mine closes, the philosophy is there has to be another mine ready to come online. Any company would like to have more mines, but eight active producing mines is good.”

Currently there are no new major claims, but there are new companies coming into the district, as well as existing companies that are expanding.

“There's the River Valley project with New Age Metals that's been going on for a while, they picked up some new ground,” she said.

“KGHM is still looking at their Victoria Project. Glencore has announced they are looking at the Onaping Depth and weighing when that can be brought into production as well. As their other mines become depleted, they are looking at replacement.”

The basin keeps yielding for those companies. Statistically, in 2016 the region produced more than $2.5 billion in mineral production. The whole of Ontario was $10.6 billion. While there are only eight mines, she said they are significant for the province's mining industry.

Mining has been going on for over a century in the region, with a focus on nickel.

There are still plenty of nickel reserves in the basin, but as energy demands shift from fossil fuels to electric, components to build batteries are now being sought, especially cobalt. The area always had cobalt deposits, she said, as they are always found with other minerals like silver and nickel, but up until recently it wasn't considered worth extracting on its own.

“Nobody thought we'd be looking for cobalt in the future,” she said. “Traditionally, prospectors looking for silver would follow cobalt because it never exists alone in deposits, it's always mixed with other minerals like silver. Follow the cobalt, you will find silver. Now it's the other way around as companies look for cobalt for the growing green energy sector to use in batteries.

“It's hard to predict what will be coming down the pipes over the years in mining.”

She couldn't say exactly how much demand has grown, or of any definite plans to mine cobalt, but as global demand increases, she said companies will start looking in advance, gauging future demand and starting the process of exploration. With proven deposits in the district there is potential for mining.

While cobalt is found with other minerals, Peloquin said mining them out does not generally cause the price of those minerals to go down on the commodity market, but it will change the economics of the deposit. It makes the deposit more profitable as whoever is mining it will get more money for the same number of pounds of ore.

“It increases the value of the deposit,” she said. “It won't effect the prices of the other metals because they have their own supply chains. The deposit becomes more valuable.”

Many of these deposits are well-known, she said, pointing to cobalt camps in the Kirkland Lake Geology district. Three of them are along the Quebec border, and two more are on the edge of the Cobalt group deposit northeast of Kirkland Lake.

“These camps were mapped decades ago and documented. With interest growing companies are heading back to test the size and feasibility,” she said.

The purpose of the Ontario Geological Survey, she said, is to act as a liaison, outreach and offer expertise to mining companies, prospectors and the public seeking information on the geological records of the province's districts.

“There's a difference between the district and the basin itself. There's the Sudbury Mining District, then there's the what I work with, the Sudbury Geology District. There are mining districts, because there are marked differences as far as regulations go, because most of the land in the south has been removed (for staking) because there are so many people that actually own land.”

In a statement from the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines, only Crown-held mining rights for privately owned property in the Southern Ontario Mining District are withdrawn from claim-staking. The Mining Act requires notification to private land owners (surface rights owners) within 60 days after applying to record a mining claim in Northern Ontario.

Peloquin said she started at the office six months ago, although she lived in Sudbury for 14 years.

Originally from Manitoba, she worked in Saskatchewan, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador and Ontario. She received her post doctorate from Laurentian University, doctorate from the University of Montreal and a master's degree from the l'universite du Quebec in Chicoutimi. She worked for many years with a junior mining company in Sudbury.

“It's a very big learning curve, but it's been good,” she said. “The Resident Geologist Program is extremely dynamic and very good and very cohesive. We have a lot of experience.”