By Dr. John Gunn

Michael Moore's recent documentary film about lead in drinking water in Flint Michigan has catapulted that city onto a growing list of places known for environmental disasters, including Chernobyl, Love Canal, Minamata, Bhopal, London with its great deadly smog of 1952, and the little town of Walkerton, Ontario, where seven died and more than 2,000 became sick because of E. coli contamination.

Positive environmental stories from specific places also exist, but like the evening news, the positive stories never get quite as much attention.

There are, however, some wonderful examples, such the Montréal Protocol and the Paris Accord, where a city's name is forever linked to an event where world leaders came together to address global threats to the environment, such as the ozone depleting compounds in the atmosphere, or the severe threats of climate change.

Sudbury, Ontario, as the recent CBC Ideas feature indicated, is another place that deserves to be on such good news lists.

Sudbury is the home of one of the largest mining complexes on the planet, where mining began in the 1880s along the rim of an ancient meteorite crater. Sudbury metals, mainly nickel and copper, were strategic metals for building ships and armaments for both world wars, but like the damage wrought by wars in Europe, the crude early smelting techniques of sulphur-rich ore devastated the Sudbury’s local environment.

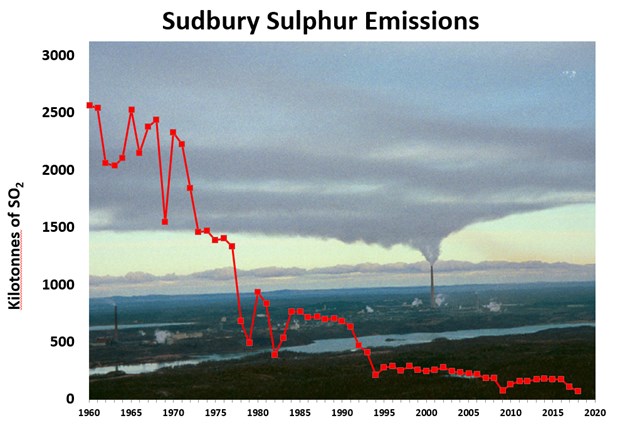

As time passed, Sudbury smelters grew to become the largest point source of sulphur dioxide in the world, with annual emissions peaking in 1960 at approximately 2.5 million tons. This staggering amount is equivalent to about 25 per cent of the sulphur pollution that all of China produces today.

The early impacts on the environment were horrendous, with the forest reduced to a near barren landscape over an area of 80,000 hectares, approximately the size of Hong Kong, and 7,000 local lakes were acidified when the sulphur fell as acid rain.

Serious, too, were the socioeconomic impacts that the negative image created for Sudbury (tagged with the nickname "moonscape"), especially after the construction in 1972 of the tallest smokestack in the world, the 381-metre "Superstack" that distributed the pollution to many distant unhappy neighbours.

However, over the past 50 years, good government regulations, innovative technologies and massive community engagement have changed this dreary story into one of the great international environmental success stories of our day.

With the mounting crisis of climate change, good news stories are increasingly rare. Air quality is now better in Sudbury than in most southern Ontario cities, sulphur emissions have, in fact, been reduced to approximately one per cent of the historic highs, and the iconic Superstack is now slated for decommissioning and removal beginning in 2020.

More than 10 million trees have been planted as part of a community-led revitalization efforts, first recognized with a Local Honours award at the 1992 UN Earth Summit in Brazil, and then later with many other conservation awards. Healthy fish populations have now returned to downtown city lakes, and the cultural life of the city is thriving.

In fact, in 2015, Stats Canada considered Sudbury the happiest city in Canada.

You might think this progress all happened at the expense of the industry, but no, the two local companies are still profitable and producing approximately the same or even more tonnage of metals than in the past. The workforce has also evolved from mainly smelter workers and underground miners to now a similar total number of people, but with fewer employed in underground jobs, and many more in small to large spinoff mining technology and service companies.

Even the Sudbury metals have undergone transformation in their use, with copper and nickel now beginning to head off to become batteries in a growing number of autonomous vehicles and contributing to other parts of the low-carbon, more electrified green economy.

Can Sudbury actually be a “mining hub” for this new cleaner economy? That would be a refreshing idea!

Dr. John Gunn is the Canada Research Chair in Stressed Aquatic Systems and the director of the Vale Living with Lakes Centre in Sudbury.