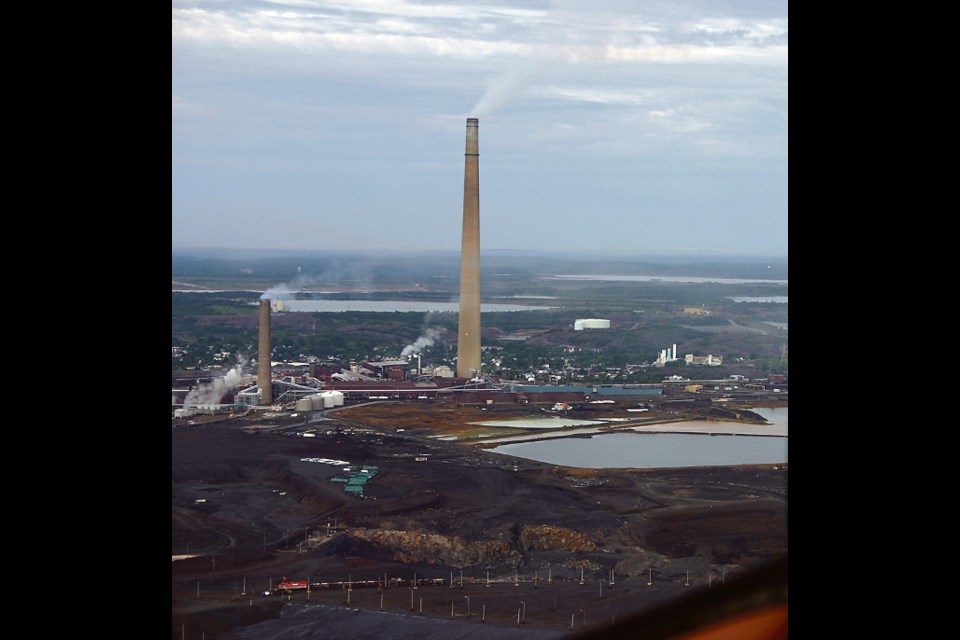

In the decades-long efforts to regreen the Sudbury basin, Vale is reporting its Copper Cliff Tailings Project using biosolids is continuing to be successful.

So successful, the groundbreaking project recently won an award and plans are in the works to apply it to other reclamation projects.

The Copper Cliff Tailings Project, a joint effort by Vale and Terrapure's solutions division, Terratec Environmental, has been running for about five years and continues to show positive and even surprising results.

“We are doing this for two reasons: dust control and covering the area with vegetation for long-term closure plans,” said Glen Watson, superintendent of environment decommissioning and reclamation for Vale Canada.

It recently won the Water Environment Association of Ontario's 2018 Exemplary Biosolids Management Award.

To win that award, Watson said, shows how important the project is, as well as how much their innovation is appreciated by the industry and environmental protection groups.

The project started with Jeff Newman, director of business development, approaching Vale with the opportunity to start a pilot re-vegetation project in the Copper Cliff tailings.

Biosolids had not been used in mining reclamation before this.

The company was interested as the tailings are difficult to regreen naturally, due to the acidic and nutrient-poor content and sandy texture of the material.

Watson explained the kind of biosolids they are using are known as class B, which includes treated sewage sludge. These are often used in farming operations in the summer for agricultural fertilizer. In the winter, however, they are sent to landfills.

“The problem with that is they are sending otherwise good material for regreening to the landfill, and the amount of space available in landfills is limited,” he said. “This diverts biosolids away from landfills and they have a year-round use.”

The biosolids had to meet the Ministry of environment and Climate Change regulations to get approval, and Vale had to work with people living in the immediate area to ensure smell and leakage didn't affect them. Watson said there was some concern over shipping sewage into the area, but Vale had already developed an in-house solution to this that helped alleviate a waste problem of their own.

“We have a lot of wood pallets lying around from shipping,” he said. “Instead of sending those off to be chipped or burned, we shredded them to be used as a carbon source and created what we call a custom reclamation mix. We monitor it over months, turn it and use fans to keep the smell under control.”

They also talked to the City of Greater Sudbury to add leaf and yard waste to the mix.

Once finished, Watson described the mix to be like common garden soil. The mix is spread over the tailings.

“It's proving to be a very quick means to encourage vegetation growth,” he said.

To control dust and odour, they cover the mix with straw, which also contains seed that has been taking root and producing plant life.

Vale has also been experimenting with agricultural seed to measure the mix's fertility. They planted hay and barley in a 70-acre wide area and harvested it last year, which he said produced a high-quality crop with no detectable metal uptake.

“It was a higher yield than what you would expect in any farming area in Ontario,” he said. “The roots are not reaching the tailings, so they are not drawing up metals from that soil.”

None of the crop will be taken off the site, however, as it is an experiment.

It does show the mix is very successful at regreening. In those areas, he said wildlife has been returning and ecosystems are regenerating very quickly.

While the Copper Cliff tailings will be closed off to humans for the foreseeable future, Watson explained it is encouraging to see how fast and safe the mix is proving to be in regenerating mine sites for the ecosystems.

They are still monitoring and capturing all water coming off the tailings, and will do so for years to come.

This isn't the first time Vale has tried a type of biosolid for reclamation. Watson explained it tried using paper biosolids with some success, but they proved to be too costly.

They also tried using fertilizer and lime to adjust tailings acidity for seeding, which was also expensive.

The provincial government was interested in this project as it would be another way to utilize biosolids on a year-round basis.

The long-term goal, he said is to use this re-vegetation technique in other areas, such as Stobie Mine, where there is less activity and Vale wants to shrink the footprint.

“There are mine areas that are 120 years old or more and have suffered vegetation loss,” Watson explained. “My long-term goal is to seek approval from the province to use it in other areas like that.”

For Terratec it was an opportunity to expand and diversify their business opportunities. Newman said much of the equipment Vale uses to make their modified mix is from Terratec, but in the beginning they were just using straight biosolids.

To help ease concerns and risks associated with transporting biosolids, Newman said they manage it through a number of factors.

“We look at things like wind directions, and through Vale, they manage a lot of our concerns,” he said. “But if we do get a call about odours, we would change our operations, as well as doing checks ourselves.”

That's a primary reason they went with partial composting. There is a reduction in odours, and makes a product they can handle with ease.

Terratec initially did blend tailings into the mix. Despite concerns over metal uptake into plant life, he said, there is very little due to high pH levels, which stops plants from absorbing too much metal.

As well, the material grown is not going into food production, so there is little risk of metal poisoning.

“If there are any questions we are very active in the research side of it. We work with academics.”

Eventually, he said they are hoping to use this model to use more biosolids in mine reclamation and sell the idea to other mining companies.