Just days before Christmas in 1958, some 14,000 Sudbury miners and their families got the news they had been praying for: the three-month strike at Inco was over.

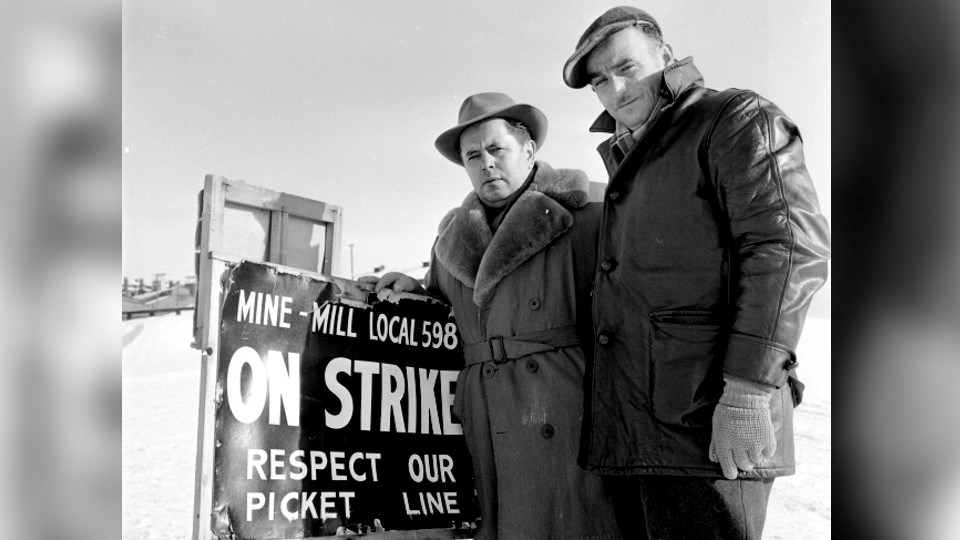

Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Local 598 president Mike Solski announced an agreement had been reached with Inco.

A three-year contract and a six-per-cent wage increase over three years was offered. This amounted to pennies on the hourly wage at the time of less than $3, but union leaders considered the settlement a victory.

The Strike of 1958 was the first major one at Inco, then the city's largest employer, and considered by historians to be a turning point in the decline of the labour movement in Canada.

Solski would be defeated as president in 1959, and in 1962 Inco workers voted to join the more moderate United Steelworkers of America.

Sudbury.com invited readers to share memories of the Strike of 1958.

Most of the striking miners have passed away but their children have vivid memories of their worried parents, fears about losing their homes or having to move in with relatives. There was no social net — OHIP was not established until 1966 — and few young families had much savings.

Some remembered their dads went moose hunting to feed their families.

Bruno Zaoral's father worked at Creighton Mine in 1958. Like many "breadwinners," his father left Sudbury to find work.

His dad, who was 29 at the time, got a job washing dishes in a restaurant in New York City.

"My mother had many relatives in Brooklyn and no doubt they got my dad the job and a place to stay. Dad paid for his room, ate at the restaurant, kept enough money for cigarettes and sent my mother the rest so she could pay the mortgage and buy food.

"When the strike was over, I remember my dad’s homecoming. The memory is clear because he brought a huge cardboard box home. Well, the box was huge to a child.

"I had to stand on my toes to see inside the bursting box; there were pots and frying pans, linens and clothing. I received a lined black leather biker jacket loaded with studs! (It didn’t take me long to ruin this jacket sliding down ice-crusted snow hills up in the rocks on my back.)

Michele Pollesel, who was nine in 1958, remembers it was a hard time for her family. Her mother had been diagnosed with tuberculosis in August, just weeks before the strike started. She and her brother went to live with relatives.

"Treatment at that time was to hospitalize (tuberculosis) patients at the (Sudbury Algoma) Sanitorium (on Kirkwood Drive.)

"My mom was hospitalized for some 14 months. When the strike hit, my dad and uncle went off to North Bay to work on a housing construction site. They came back to Sudbury on the odd weekend.

"Children were not allowed to go into the San, so my brother and I had no physical contact with our mother during all that time. Quite honestly, I felt like we had been orphaned. Although our young aunt did her best to care for us, it was not a happy time.

"We would lay in our beds at night and recite the rosary, in hope that our situation would ameliorate."

Wayne Hugli wrote, "I was 10 years old and our family was living in Coniston. My parents told us it would be a smaller Christmas for us that year, but I remember how the union and community groups did their best to ensure everyone had presents on Christmas Day."

"I was only seven and remember the worried look on my dad's face vividly," said Anne Marie Gauthier. "The major concern was the fight for medical benefits. Four years earlier my mother had passed and my dad was left with a hearty hospital bill. As much as people dislike unions, none of us would have the benefits we enjoy today (without them)."

Doreen Pagnutti wrote, "My parents had tenants who were impacted from lack of business during the strike. The man was a TV repairman in those days and because of the strike had less income and could not pay the rent. So rather than lose a good neighbour and tenant, my parents did not evict them and told them they could pay the rent when the strike was over and when they could afford it.

“These are hard times for a lot of people these days. We need to step forward when we can and help our neighbours."

Terry Dupuis remembered the kindness of local businesses during the strike. He wrote,"Here's to Giannini's IGA and Picollo's Red and White grocery stores in Levack that looked after the town's people during the strike."

Elizabeth Quinlan's father was a research director with Mine Mill in the 1950s. She is now an associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan and writing a research paper on the Strike of 1958 with a focus on memories of people who lived through that period.

"The strike highlights the dignity of Sudburians; their strong sense of justice and willingness to make sacrifices," she said.

"In reflecting back on the strike, people have said to me, 'perhaps it would have been better if the strike never happened, but we survived and in many ways we’re stronger for it.'

"It wasn’t just the strikers who made sacrifices: wives who went to work, in some cases just shortly after giving birth; store owners who gave lines of credit; others shared produce they grew in their gardens with those who needed food; women made Christmas dinners for neighbours.

"There were many sacrifices. But people developed new skills and learned they had strengths they didn’t know they had.

"People are telling me the strike was very difficult, but they also learned something about how to be frugal, how to stretch a dollar, and also they learned about their family members and others by having to pull together and help each other out."

Quinlan is continuing her research and would like to hear from people who remember the Strike of 1958. You can reach her at inco1958strike@usask.ca.

— Sudbury.com