April 28th is the International Day of Mourning, where we pause each year to remember workers killed on the job or as a result of occupational disease — numbering 1,000 annually based on workers’ compensation statistics from accepted claims. We vow each year to mourn for the dead and fight for the living. For the many worker deaths from occupational disease that go officially unrecognized, however, mourning the dead is a complicated and often unachievable task for the families left behind.

“I find that while I am working underground I am continually spitting up blood and other dark substances, which could be a result of silicosis. Would you be kind enough to look into my case, to find out if the Mine has any responsibilities towards me.”

It was Dec. 21, 1967 and Andrew Tabaka had already spent 11 years underground at Kerr Addison Mine in Virginiatown, Ontario when he wrote this letter to his Member of Parliament, Arnold Peters. The month prior, Tabaka had left the mines due to a heart condition and after a doctor’s warning that he “could not expect to live more than a year” if he continued mining. He began vocational training through the Manpower Centre in Elliot Lake, but soon left due to family circumstances and financial hardship.

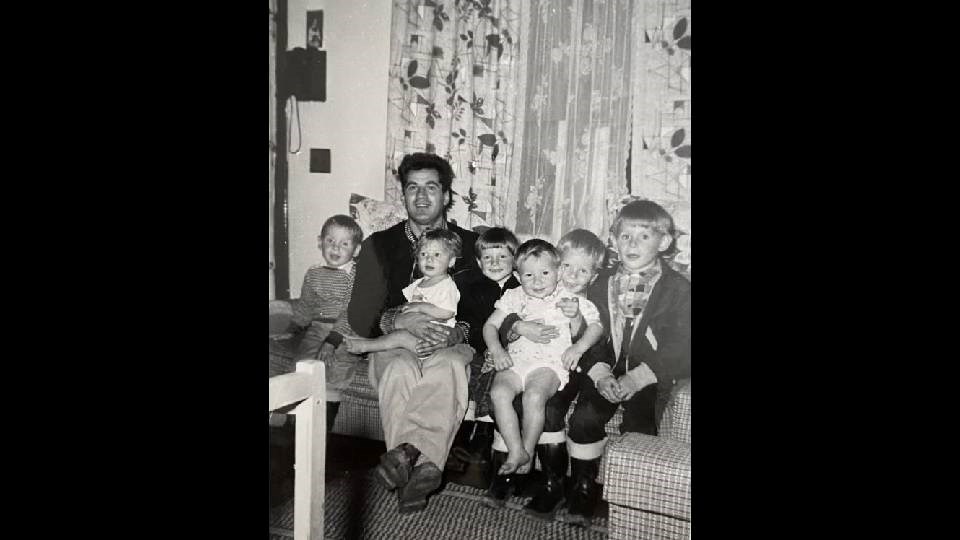

Tabaka returned to mining, writing to Peters that “I then was forced to take employment again as a miner at Upper Canada Mines. The Kerr Addison Mine refused to rehire me because of my physical condition.” Tabaka had a family to support as a father of six children. His family reports that he was a lifetime non-smoker. That lifetime was short. Tabaka was 46 years old when he died in August 1970.

Half a century later, his children still wonder whether their father had silicosis and if the heart condition that took his life was related to the dusty working conditions and exposures that he faced as a miner. His family will never have those answers. Tabaka’s medical records no longer exist, destroyed according to legislated record retention requirements. He died without a will, making it difficult for his family to establish the legal authority necessary to access other potential sources of information, such as prior workers’ compensation claims. Andrew Tabaka’s death will never be counted as one of the 1,000 Canadian workers whose work-related deaths we remember each year on the Day of Mourning.

Occupational disease is insidious in nature, developing slowly and often going undiagnosed until many years after the worker is exposed to toxic elements on the job. This makes it difficult to identify and combat workplace illnesses, particularly in the absence of a comprehensive system designed to track workplace exposures and monitor worker health outcomes.

Occupational diseases are detected through research. Research depends on data. Data is gathered through effort.

We need to expend that effort to gather that data to enable that research to identify occupational diseases and in doing so, to protect workers. We need to build a comprehensive, nationwide system that documents what workers are exposed to during the course of their labour and compiles their health outcomes. We have failed to do this for decades, leaving the sick and dying workers themselves as evidence of the existence of occupational disease.

Making the effort to investigate the relationship between what workers are exposed to on the job and what health impacts those exposures may have on them is not simply an exercise to provide families like the Tabakas with answers and compensation where warranted, although that goal alone is sufficient and worthy. There are multitudes of families like the Tabakas. Families whose loved ones became sick and died from the dusts, chemicals, fumes, carcinogens, particulates, solvents, and other toxic exposures that they experienced at work. Deaths that are seldom investigated to determine if there is a workplace link. Deaths that fall outside the 1,000.

In fighting for answers for workers who have died, we are learning the information that we need to protect the workers of today and the future. Maybe then we can fully mourn our dead.

— With thanks to John & Nicole Tabaka for sharing Andrew’s story

Janice Martell is a researcher and occupational health coordinator with the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers, and the founder of the McIntyre Powder Project.