Noront Resources doesn’t intend to dig open-pit mines in the James Bay lowlands even though the abundance and the proximity of the rich chromite ore bodies to surface might dictate otherwise.

“It’s a natural ore body for open-pit mining,” said Noront president-CEO Allan Coutts during the Great Sudbury Chamber of Commerce's Procurement, Employment and Partnerships Conference on Feb. 6.

“However we’ve said quite categorically, we’re not going to approach it as an open pit.”

As the largest landholder in the Ring of Fire, Coutts said the thickness of their string of chromite deposits range between 10 and 30 metres, and come right to surface.

If they were designing these mine projects 10 to 20 years ago, Coutts said these deposits would certainly be mined by open pit methods.

But pits generate plenty of waste rock, often disturb a large swath of land, and the water that seeps into the pits has to be treated before it’s pumped back into the environment.

Surrounding First Nation communities had “significant concerns” about this, said Coutts. “We just don’t think that’s the way to go about mining this.”

In taking into consideration the wants and needs of the communities that they want to partner with, Noront redesigned their projects to address those concerns.

“There won’t be an open pit and waste rock piles, and we have committed to putting the tailings back in the ground so there’s no tailings enclosure at all,” said Coutts.

Noront’s development strategy is to bring its Eagle’s Nest nickel-copper mine online first, followed by its chromite deposits, beginning with Blackbird.

If the provincial government stays true to its road-building timetable next year, Noront plans to start construction of Eagle’s Nest at the start of 2020 with production slated for mid-2022.

Noront’s mantra is to develop the first mine in a way that’s “progressive and successful and inclusive.”

“You get one shot to do things right,” he said. “We want to do this first mine right.

“We want this to be a shining success and we want this to be the first of numerous mines in the area.”

As the key mine developer in the region, Noront has a pipeline of projects in chrome, nickel-copper, copper-zinc, and vanadium.

Their intentions are to keep their imprint on the land as small as possible.

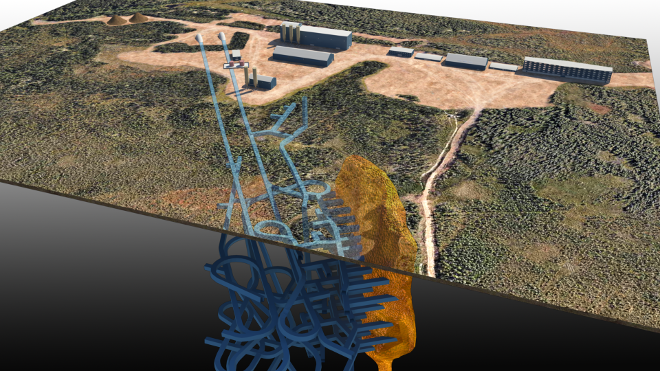

Coutts said Noront is adopting an underground bulk mining method, similar to LKAB’s Malmberget-Kiruna Mine in northern Sweden, where waste rock is used to fill the cavities that are created when ore is mined.

Having community buy-in, through Ontario and Canada’s rigid environmental and permitting process, plays an integral role in getting project approvals.

In the long run, Coutts doesn’t believe that going with underground methods will be all that costly.

“It’s a trade-off. We think it’s better overall from a permitting point of view, for our relations with First Nations point of view, and (from) a legacy point of view to bear a bit more cost in the early days and do that from underground. And we still believe there are adequate margins to do that.”

As a portal-and-ramp mine, Eagle’s Nest is considered a “modest” deposit with an anticipated 20-year mine life, Coutts said.

With two base metals smelters available in Sudbury, “it’s a natural first mover for us.”

The cash flow from the sale of nickel would be earmarked to bring its more extensive – and expensive – chromite deposits into production, which have 100 to 200 years of mine life.

With no ferrochrome smelters in North America, and Noront currently evaluating Northern Ontario cities to place a $1-billion development, Coutts said it’ll be a huge investment to get those deposits producing.

Economics and commodity prices might also dictate which deposits go into production first.

“We have some flexibility over which project gets done first. “Is it the chromite project? Is it the nickel project? We’ve got a copper-zinc project we’re very excited about as well.”

With the number of discoveries in the Ring of Fire at 20, Coutts said not all will become mines.

But the size of the mineral belt indicates it has the potential to be on the same scale as mining camps like Sudbury, Timmins, and Red Lake.

Noront has no plans to build an Elliot Lake-style company town at the mine site.

It will be a fly-in/fly-out operation. A work rotation schedule hasn’t been worked out but area First Nations – who will surely find employment there – will have some input. “We’d rather see investment in the local communities around the mine.”

Coutts told the crowd the federal and provincial governments are working to upgrade the housing and community infrastructure.

“That’s the best way to go.”

Webequie and Marten Falls will eventually be connected to the mines by a proposed north-south access road, funded by the province, as announced last August by Queen’s Park. The detailed engineering and environmental assessment of two access corridors have started.