Danny Hway vividly remembers the impact McIntyre Powder had on his father, Nicholas, who worked at Timmins’ McIntyre Mine for 47 years.

At home, his dad wouldn’t speak of it, but he didn’t need to. His grim appearance at the end of every shift did the talking for him.

“He’d come home and his hands were black all the time, and any exposed skin was black,” Danny recalled. “He’d be coughing all the time and, blowing his nose, it was black all the time. He didn’t really want to talk about it — (that’s) life, right?”

Nicholas was one of thousands of miners across the North who were required to inhale the finely ground aluminum dust as a condition of their employment. But for him the stakes were higher than for most: preparing the powder for dissemination was his job.

On most days, Nicholas was sequestered in a small, dirty shack on site at McIntyre Mine, where, for eight hours a day, four months of the year, he pulverized aluminum pellets into the dust that would be shipped to mines around the world.

“I was told, by other miners I talked to, they would come and check on him and open the door, and they felt sorry for him, because you couldn’t see him,” the room was so blackened from the dust, Danny said.

On busy days, Nicholas had help from a cadre of about 12 more workers, among them Fern and Rolly Carriere, brothers who worked at the mine for 11 and 15 years, respectively. The three were introduced for the first time during the May McIntyre Powder Clinic in Timmins, which brought together former miners who were seeking answers about the use of McIntyre Powder at the mines.

“They used to deliver a big box or barrel of aluminum pellets, and (Nicholas) was the one who would put them into the ball mill,” Fern recalled. “Nick would put all the pellets in and he would put a big pot underneath and just flip it over, and the powder would fall down and he would fill the cans.”

It was Fern and Rolly’s job to seal the tins before dumping them into a tub of sawdust, which cleaned the dust off the canisters in preparation for delivery. The sawdust was later taken to a dump site and burned.

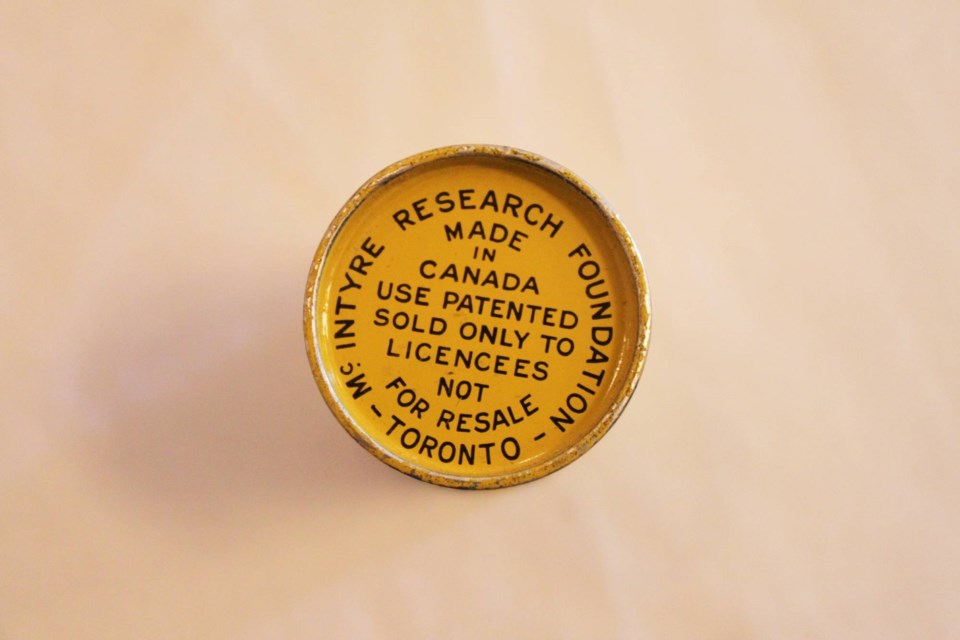

Packaged 50 to a box, the tins would be affixed a label and sent to the train station or post office to be shipped out. Fern recalls being impressed by the extent of the enterprise.

“We were surprised when we saw (packages for) South Africa, Mexico, Brazil, and we used to say, ‘Oh my god, Mr. Newkirk’s got a good business here,’” he said of the mine’s manager at the time.

When it came time to disseminate the powder to the miners, it was usually in the mine dry while the miners were getting ready for their shift.

“They used to blow that in the dry, let’s say, 5 o’clock in the morning,” Fern recalled. “They would blow maybe three, four cans into the air and they would recommend that you would walk into McIntyre dry, breathe deep while they’re getting dressed. You used to bring down your clothes, and your clothes, your rope, your seat, everything was black.”

Like Danny, Nadine Del Bel Belluz recalls her dad, Michael Brisbois, bringing home tales of the powder from work.

“I actually remember growing up listening to him, and he and my mom would sit at the table and talk about his day, and he always talked about this aluminum dust,” she said.

Her dad was first exposed when he signed up at McIntyre at the age of 17. By 1967, he was working at Kidd Mine, then owned by Texas Gulf Sulphur Corp, recalls Michael’s wife and Nadine’s mom, Brenda.

“At the mine, he did some welding, he drove trucks for a while, and then he went underground, and he used to put in a lot of the tracks, and then the ventilation ducts,” Brenda said. “I think that’s where the welding part came in and a lot of the stuff they used was aluminum.”

As he reached his 50th birthday, Michael’s memory started to falter, and family members became concerned. But it would be another four years before a diagnosis would confirm the family’s suspicions.

“He had it at 50, but he wasn’t diagnosed until 54,” Nadine said. “He had signs at 50, but who gets Alzheimer’s at 50 years old? We lost him really young.”

Doctors searched for the trigger behind Michael’s neurodegenerative disease, but there was no history of Alzheimer’s in the Brisbois family, and physicians could not make a link to genetics.

“They stipulated that his Alzheimer’s was brought on by outside factors,” Nadine said. “That’s what they said: it’s not hereditary; it was brought on by ‘outside factors.’”

The family teamed up with the Office of the Worker Adviser to submit a compensation claim on Michael’s behalf, but, like so many other former miners, he was denied because the WSIB does not recognize a link between aluminum and neurodegenerative disease.

Over the next seven years, Brenda cared for her husband at home, but Michael was deteriorating rapidly. Then one Christmas, he went to spend a few days at Golden Manor, a long-term care facility in Timmins, to provide respite for Brenda during the holidays. He would never come out of the facility.

Michael spent another 10 years at the Golden Manor where, little by little, the man the Brisbois family had known as an attentive, loving father and husband eventually disappeared.

This past January, Michael died of his illness. He was 70 years old.

Danny’s father Nicholas is no longer living either. In retirement, he developed cancer of the esophagus, which he received treatment for, but eventually he succumbed to his illness.

“They did an autopsy, and he had lung cancer, too,” Danny said. “But he had all sorts of other stuff in his lungs, too.”

Fern and Rolly have had their own share of health issues; between them they’ve had two heart attacks, a stroke, and limb numbness. Two of their other brothers, who also worked in the mines, have since died of heart disease, and a fifth brother, who worked outside the mining industry, remains healthy.

For Janice Martell, finding answers for former families of miners like Nicholas Hway and Michael Brisbois is a cornerstone of the McIntyre Powder Project, an initiative she started in response to her own father’s 2001 Parkinson’s disease diagnosis.

Over the last year, she has collected more than 250 names on a voluntary registry that compiles miners’ names, employment histories and illnesses that she suspects stem from their employment in the mines.

It’s important to hear their stories, she says, not only to collect anecdotal evidence for a potential research study, but also because, as their health deteriorates, the stories could soon be lost forever.

“This may take years to go through, and we’re losing voices,” Martell said. “I’ve lost six people on my registry in a year.”