Information is still being gathered from the McIntyre Powder clinics, which document the lives of miners who inhaled aluminum dust while working in mines across Canada. But an early trend shows a higher incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) than in the general population.

ALS — also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease — is a rapidly progressing neuromuscular disease that paralyzes muscles in the body, eventually leading to death. There is neither a cure nor an effective treatment for the disease, which affects about 2,500 to 3,000 Canadians.

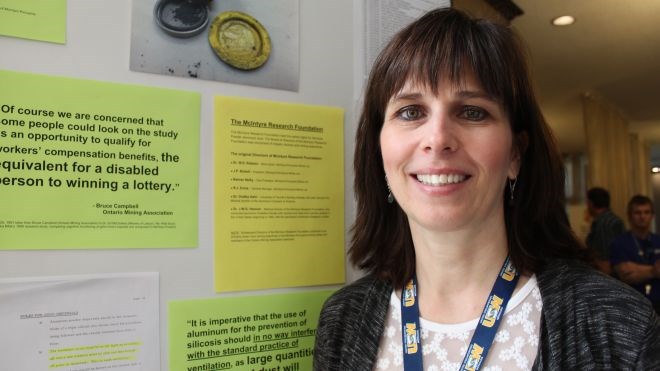

Of the 344 former miners registered with the McIntyre Powder Project, four have been diagnosed with ALS, noted Janice Martell, the creator of a registry that documents miners’ health histories.

“Even though four sounds really small, it’s statistically quite large for ALS,” Martell noted.

According to ALS Canada, an ALS patient and research advocacy group, the number of new diagnoses of ALS sits at two in 100,000 people per year. In addition, roughly two in 100,000 people die of ALS annually.

That puts the incidence of ALS in the McIntyre Powder group higher than the general average.

There hasn’t yet been any scientific interpretation of those numbers, and so it’s inappropriate to make any direct correlation between aluminum and ALS at this point. But Martell said it highlights the benefit of the project’s work.

“Even though the people that we're studying are people who were exposed to the aluminum dust as the criteria for OHCOW’s (Occupational Health Clinics of Ontario Workers) involvement in this group of McIntyre Powder-exposed workers, we're actually gathering a much wider information base,” she said.

“The workers who worked with aluminum dust may have worked at 15 or 20 different mines and were exposed to a swill of toxic chemicals, and we're gathering that information.”

Martell believes that could lead to discoveries of additional trends arising from other chemicals miners were exposed to on the job.

There are now 344 names on the volunteer registry, and the list of exposed workers established by OHCOW has reached 300. Most of those names were gathered in Timmins in May and in Sudbury in October, at all-day clinics where miners could voluntarily have their work and health histories recorded.

Those clinics were sponsored by the United Steelworkers, and it’s unlikely that one-stop clinics of that size will be held again. But miners can still be part of the registry, and Martell is still actively collecting names for the list.

Participants can first call Martell at 1-800-461-7120 to pre-register. Participants will be sent consent forms to fill out, and from there they will be referred to OHCOW, whose nurses and occupational hygienists will follow up with miners.

OHCOW is currently in the process of seeking funding from the WSIB to further its work on McIntyre Powder, which Martell calls “ironic,” since it’s the WSIB that’s turned down worker compensation claims related to aluminum dust in the past.

But she’s hopeful that funds will come through to continue the work she’s started.

“I hope they get some monies dedicated to this so that we can actually do the work to compile the database to see what kinds of trends there are, and gather the medical evidence and attract the researchers,” she said.

Martell has taken a four-month leave of absence from her job to focus on the McIntyre Powder Project, time she said will be used to follow up with inquiries and help OHCOW where she can.

For Martell, whose father’s Parkinson’s diagnosis inspired the project, it remains a matter of integrity.

“It's the justice of the whole issue,” she said. “Really, until you make it costly for the WSIB to look at this, and the Ministry of Labour to get on board with addressing this issue of the aluminum dust exposure, nothing's going to change.”