The Kirkland Lake Adams Mine is still an environmentally sound site for landfill, said Gordon McGuinty, businessman and former owner of the open-pit mine in northeastern Ontario.

“We lost a world-class opportunity,” McGuinty said about his 14-year ordeal to turn the abandoned iron-ore mine into a landfill for Toronto’s garbage. “There wasn’t anything that was environmentally as sound as the Adams Mine landfill and there wasn’t anything that went from a system using the Ontario Northland and CN Rail … in this province that could touch it, and there still isn’t today.”

McGuinty has written about his experiences in his recently released book, Trashed! How Political Garbage Made the United States Canada’s Largest Dump.

Today, southern Ontario’s Highway 401 corridor is a busy place where trucks carry 4 million tonnes of Toronto’s garbage to Michigan every year.

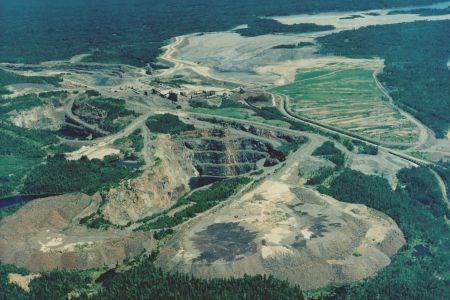

His belief in the project stands as strong today as it did in 1989, when he and his business partner Maurice Lamarche stood at the crest of the South pit that spanned 1,800 feet across and 600 feet deep, astounded by its vastness, capacity and potential to create economic development in the area.

Located about 11 kilometres southeast of Kirkland Lake, the Adams Mine produced 21 million tonnes of iron-ore pellets between 1964 and 1989. After its closure, McGuinty and Lamarche saw potential for a 20-year landfill deal as well as an industrial recycling depot for Toronto’s garbage.

Logistically, the garbage would be brought up by the Canadian National Railway and transferred to Ontario Northland’s rail service. Years before, iron ore had been hauled south along the same track from the mine to Dofasco, a steel manufacturer in Hamilton.

Coincidentally, the City of Toronto was running out of landfill space at its Keele Valley site, and began looking for a “Made-in-Ontario” solution to solve its imminent garbage crisis.

What seemed the perfect match, quickly became a series of political “earthquakes” to which McGuinty attributes the demise of the project.

“Every one of them (earthquakes) happened because of politics,” he said. “They didn’t happen because the Ministry of Environment, staff scientists and hydrologists hadn’t approved it. It didn’t happen because City of Toronto’s staff hadn’t bent over backwards to do their due diligence. It all happened because at the last minute, the politicians couldn’t handle the heat.”

His story details the trials and tribulations of business dealings, environmental approvals and political rhetoric experienced by both his companies involved in the project - Notre Development Corporation and Rail Cycle North - over the course of four provincial governments and project capital spending that pushed $20 million.

In the end, it took the government of his second cousin, Dalton McGuinty, to pass Bill 49, the Adams Lake Mine Act, which prohibited the disposal of waste at the site and prevented it from ever being used as a landfill. But Gord McGuinty said he’d do it again.

“I have no axe to grind. It is what it is, but I’m as convinced to this day, or more so, that we lost a real opportunity.”

As passionate as McGuinty still remains about what could have been, Timiskaming-Cochrane MPP David Ramsay continues to be staunchly opposed to the project. Ramsay received a complimentary copy of the book this summer, but had yet to read it when Northern Ontario Business contacted him in August.

Ramsay was even interviewed by McGuinty for the book.

McGuinty blames Ramsay and Jack Layton, a former Toronto councillor and current leader of the federal New Democrats, for obstructing and killing the project and the cancelled garbage contract with the City of Toronto. He described Ramsay as a political opportunist up until 1995. He claims the MPP changed his position in the middle of an election because he succumbed to public pressure from the Temiskaming farming community in order to preserve his seat.

Ramsay said he felt waste management was a municipal issue, not to be dictated by the province. He said he was initially interested in the recycling aspect of the project and supportive of the process to explore the ability of the concept because it was a relatively new science at the time.

“There were some very intriguing ideas at the beginning, but as time went on, it became apparent that there was just going to be a dump,” he said. “So over time, the whole concept of the project had changed. And once that happened, I stopped supporting a process of exploration to being dead set against (it).”

A concept that he said required active pumping for 90 years and another 200 years of gravity drainage, in his view, was an absurd project. He said he had concerns about the leachate leaking into the ground water, leaving him convinced that 20 years worth of jobs wasn’t worth the environmental risk.

When reminded that a provincially issued Certificate of Approval had been granted, showing the pit did not leak, Ramsay responded that it would eventually over time.

“The great doubt that people had, including myself, was ‘Could you maintain the control of the leachate for 60 to 90 years after pumping time and 200 years of gravity drainage?’”

Despite the fact that $8.5 million was spent by McGuinty on an environmental assessment proving the pit didn’t leak, it was this fear that sparked a well-organized environmental movement that knew how to use the media to spin its message, and eventually, won the struggle to stop the project, he says.

McGuinty admitted he didn’t communicate his message as well.

“We have the right to fight back and I don’t think I fought back the way I should have,” he said, and given a repeat opportunity with the knowledge gained, he would manage those issues better and more aggressively.

He plans to use his “lessons learned” to provide “Island of Truth” workshops in a consulting capacity for other companies or municipalities considering large projects.

“What is the Island of Truth of your project? Do you really know what you are doing when you roll it out so when you get those queries from the press or the political side, can you answer them?”

He said he is getting positive feedback on the idea.

In the meantime, McGuinty resides in Canmore, Alberta and retains a North Bay office for Notre Development Corp. He is currently investigating some business opportunities in Ontario. He plans to speak about his book and participate in various speaking engagements on waste management while developing the workshops.

Even today, the project still lives on in the courts. Pennsylvania’s Vito Gallo, one of the last investors of the Adams Mine and current owner of the property, filed a $355-million arbitration pending against the Canadian government under the North American Free Trade Agreement as a consequence of Bill 49. It will go to a tribunal hearing in the spring of 2011.