The green energy movement has sparked a new phase of exploration in a corner of northwestern Ontario.

A handful of mining exploration companies are actively probing the granite rocks between Kenora and Sioux Lookout in searching for rare earth elements and rare metal mineralization.

Even cobalt is making an appearance.

One of the companies in the mix is Puget Ventures in the Werner Lake area, north of Kenora.

President Erin Chutter said the string of properties her Vancouver junior company has packaged together since 2008 is capable of developing into a sizeable cobalt deposit with multiple mines, “like pearls on a necklace.”

The Vancouver junior has big plans to become Canada’s only primary cobalt producer with its centrepiece project, the past-producing Werner West Cobalt Mine.

They’ve assembled a 60-kilometre-long belt of properties covering two former mines and five historic deposits and resources, including three cobalt and two nickel-copper-platinum group metal deposits.

Werner West had a sporadic mining history in 1929, 1932 and in 1940-44, producing grades as high as 20 per cent cobalt.

Cobalt was a highly strategic metal used by the U.S. military to make nuclear weapons. Production numbers from Werner Lake were only declassified in the 1990s, said Chutter.

Werner West has historic non-compliant reserves and resources totalling 1.1 million tons of 0.31 per cent cobalt, 0.29 per cent copper, and 0.011 ounces per ton of gold.

Today, cobalt is still considered strategic, but for more peaceful consumer items such as rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, solar panels and wind turbines.

Over the year, few analysts have followed the commodity, but the fact that the London Metals Exchange began trading cobalt last February is proof that the grey metal has a rich future and a growing following.

“We feel we’ve timed it nicely,” said Chutter.

With cobalt prices fluctuating this summer between $20 and $22 a pound, and with all forecasts indicating strong prices for five years, Chutter said it shouldn’t be a problem to stay above their $12 economic threshold.

With 70 per cent of the world’s cobalt supply in conflict-striken or unstable countries like Zambia and the Congo, prices should stay high for a while.

“We’ll push the project hard as long as prices stay strong,” said Chutter.

The former Gordon Lake Mine – active in the 1960s for nickel, copper and PGEs – is east of Puget’s land package, and some of the underground mine working runs under their property.

It’s not exactly a turnkey project, but it’s pretty close. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Canmine Resources spent $12 million drilling off the deposit, upgrading an access road, then driving a decline shaft and building underground drifts, surface buildings and settling ponds until cobalt prices tanked and with it went the project.

Canmine went bankrupt in 2003 and liquidated its assets.

“We are the lucky recipients now that cobalt prices are very robust,” said Chutter.

The 2008 global economic crash proved to be a boon for the company, allowing them to pick up some prime properties that suddenly became available.

They spent last fall and winter drilling the property to re-prove the historic deposit numbers before engineering can begin. Prospecting this summer will look at newly discovered zones that their geologist believes may be possible strike extensions.

A formal resource estimate is expected out this fall.

“We have a sense this is a long linear cobalt structure,” said Chutter. “I can’t tell you how rare a primary cobalt deposit is. There’s very few of them in the world.”

Chutter said Werner Lake is only one of two active primary cobalt deposits in North America. “It’s sort of a geological quirk of nature.”

This growing demand for green industry metals for electric cars and electronic goods has opened up a new vein of exploration in the Kenora district, said Craig Ravnaas, district geologist with the Ontario Geological Survey.

Besides cobalt, there are a handful of juniors searching for rare earth metals and rare earth elements among the 67 active exploration projects in the district.

“There are 210 known rare metal occurrences across Ontario; the bulk is in northwestern Ontario, and most of that is in the Kenora district,” said Ravnaas.

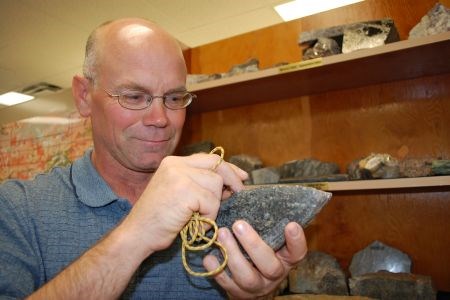

He’s sought to educate prospectors and mining companies on how to recognize and differentiate between rare metals and rare earth elements based on their geological settings and associated rock.

Rare earth elements and rare earth metals are used for hybrid cars, solar cells and magnetic resonance imaging. Lithium is a key rare metal used in batteries, glass, ceramics and as an additive to make aluminum.

“It’s a funny bird,” said Ravnaas. “The market doesn’t understand it but if there is potential for it, then we have lots of it up here.”

They are found in pegmatite granite found in great abundance in the northwest. It has caused juniors like Delta Uranium to re-evaluate their assay results. Their analysis of grab samples taken in 2008 now shows rare earth mineralization.

The best known occurrence of rare metals is north of Kenora at Separation Rapids, where Avalon Rare Metals and Gossan Resources are working ground thought to host one of the largest pegmatite deposits in the world.

The rare metal-bearing rock almost follows a trend shadowing the Trans-Canada Highway.

There is also a pegmatite field near the Dryden Airport and another at Raleigh Lake, west of Ignace, where a cluster of three juniors – Consolidated Abbadon Resources, King’s Bay Gold and Mainstream Minerals – are in various stages of staking, sampling and surveying.