Hard rock miners in Northern Ontario who developed Parkinson’s disease after inhaling McIntyre Powder at work have overcome a major hurdle to receiving compensation from the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB).

On Feb. 2, the Ministry of Labour announced that a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease that has been linked to work-related exposure to aluminum dust known as McIntyre Powder will be formally recognized as an occupational disease under the Workplace Safety and Insurance Act.

That means that the onus to prove exposure is no longer on the workers, and those miners submitting claims for compensation should have their requests processed faster and more efficiently.

“Anyone in our province who falls ill on the job should have the confidence that they, and their loved ones, will be taken care of,” Labour Minister Monte McNaughton said in a news release announcing the change.

“That is why I am so pleased to announce a change that will guarantee compensation for workers who have suffered unfairly as a result of exposure to McIntyre Powder.

“And today is just a start — our government will continue to make investments to help identify and recognize occupational illnesses and support those who have been injured by exposure on the job.”

Janice Martell, a Sudbury-based worker advocate who's the founder of the McIntyre Powder Project, was overwhelmed at learning the news.

“I wasn’t expecting this,” she said.

In 2020, the results of a WSIB-commissioned study, led by researcher Dr. Paul Demers, definitively concluded there is a link between the inhalation of McIntyre Powder and the development of Parkinson’s disease.

Since then WSIB adjudicators assessing claims have taken that into consideration, referencing a special internal document to weigh claims.

But this newest announcement from the Ministry of Labour gives more strength to McIntyre Powder-related compensation claims, Martell said.

“This elevates it beyond WSIB policy,” she said.

"That policy is just an instruction booklet that they could change at some point, whereas this is entrenching it in law that is part of the regulations attached to the Workplace Safety and Insurance Act.”

Want to read more stories about business in the North? Subscribe to our newsletter.

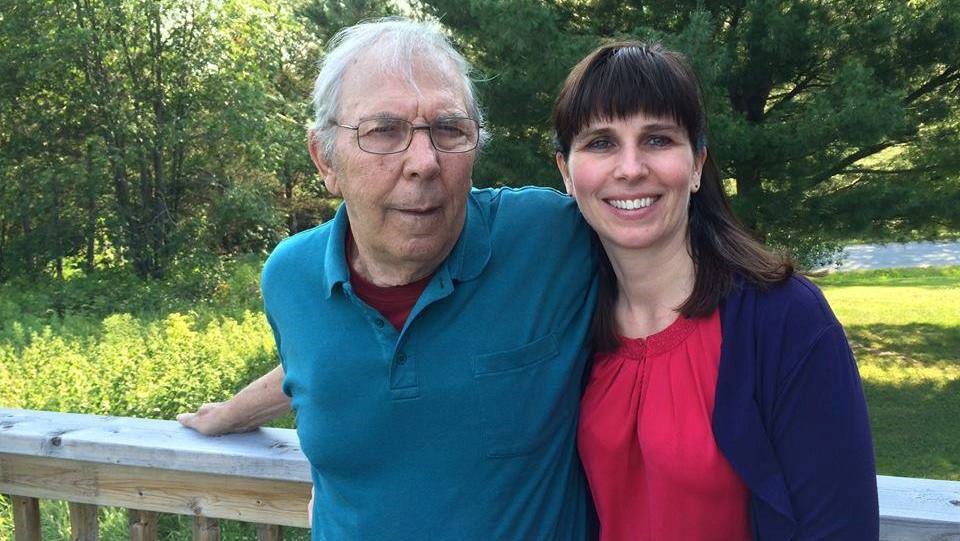

Martell has been researching McIntyre Powder since 2014 when she learned about the substance from her father, Jim Hobbs, who told of having to inhale the dust as a condition of the job during his work as a uranium miner. He later developed Parkinson's disease and died of the illness in 2017.

Invented by mining executives as a potential preventive measure against the lung disease silicosis, the practice was adopted at mines across Canada and in various parts of the world between 1943 and 1980. It was later debunked as ineffective and abandoned.

But scores of miners developed various neurological and respiratory illnesses. Martell suspected McIntyre Powder was the cause.

Though this most recent development brings some comfort to Martell and the miners who were exposed, challenges still exist.

Because the practice of administering McIntyre Powder continued over several decades, many of the cases involve older or deceased claimants whose medical records may no longer exist, Martell noted.

“If you have an estate whose husband died of Parkinson's, McIntyre Powder-exposed, they should be eligible for this,” she said. “But they have to show that they have a Parkinson’s diagnosis, and if that person died more than 10 years ago, usually those medical records are destroyed, so it's a challenge."

Still, it’s rewarding, she said, to see miners and their families finally get some compensation to pay for home care or nursing aid while they remain living, a luxury her father didn’t have.

Yet the value of a successful claims process goes beyond money, she added.

In many cases, the recognition by the WSIB of the legitimacy of the claim is as much a relief as the financial compensation.

"My own personal healing from the trauma around dad’s life was helped tremendously by the WSIB acknowledging that his Parkinson's was work-related,” she said. “Just having that acknowledgement gave me the space to heal, and I'm in a much better place personally in my life because of that.”

Last fall, Martell joined worker advocates from across the province in forming the Occupational Disease Reform Alliance (ODRA), which comprises workers and families who have been impacted by workplace illness.

In addition to the miners impacted by McIntyre Powder, the group includes construction workers who built a boiler at the Weyerhaeuser pulp and paper mill in Dryden in the early 2000s; steel mill workers in Sault Ste. Marie; and former employees of now-closed Neelon Casting, which made brake parts, in Sudbury.

The group’s aim is to get a number of changes made to WSIB policy, including the recognition of disease trends in workplaces and processing claims resulting from multiple exposures.

To this end, Martell is hopeful that McNaughton stays true to his promise that this most recent announcement is “just a start” of the process to have more occupational illnesses recognized as presumptive under Ontario law.

Martell was surprised to receive a personal phone call from McNaughton on Feb. 2 to inform her of the change in policy and was moved by his words of condolence for her father’s experience.

She said it was the first time a person in a position of influence had offered her kind words on the matter.

"We didn't get here overnight and we're not going to get out of it overnight, but it’s a tough sell for people who have been waiting that long,” she said. “We want action now.”